On paper: [https://arxiv.org/html/2505.23444v1]

A fix to CryoEM’s problem of scarce high-quality data. Sorry if I mangled anything.

A Bit of Background

Single-particle cryoEM has gotten better over the last decade, going from 30 Å blobs to 2–3 Å reconstructions. But raw micrographs are still tainted with noise:

- shot noise under low-dose conditions (which thin ice can contribute to)

- ice-thickness variations which create uneven background contrast across the micrograph

- CTF oscillations from microscope optics which can enhance some frequencies while cancelling others. Creates alternating bright/dark rings.

Recent efforts have focused on replicating this noise when artificially synthesizing cryoEM data, but current models don’t really do this effectively. They rely on oversimplified Gaussian noise. For instance:

InsilicoTEM (Physics-based)

- Loads PDB model you give it ⇒ spins the molecule to random angles and calculates a multi-slice electron-scattering calculation for each one ⇒ turns every shot into a grey 2D shadow, and then warps shadow with the same CTF as microscope ⇒ sprinkles poisson/shot noise so final picture looks like a real micrograph.

- What it can’t nail: physics run for every angle means heavy computational costs; only single-particles, and doesn’t account for clumping/gradients/other junk. Relies on basic Gaussian noise.

LBPN (Latent Black-Projection Network)

- Kind of like a GAN, useful for tomography where you can’t image from all angles as it focuses on cellular variability and missing data orientations.

- What it can’t nail: Focuses more on geometric completeness as opposed to authentic noise, computationally expensive.

VirtualIce (Hybrid)

- starts with real blank vitrified-ice photos from actual cryoEM images⇒ randomly throws particles onto that canvas, making them overlap, crowd, or stick to surface ⇒ pastes synthetic projections of each particle on top. It’s fast, but because it skips physics.

- What it cant nail: Signal decay through ice, CTF oscillations, and other quirks are faked with just Gaussian blur. Also can’t vary noise across FOV or emulate radiation damage.

CryoGEM

- Introduces a physics-backed generative framework that better models noise distributions, but its GAN-based formulation lacks bidirectional constraints (so the generated image can’t be reversed back to the original structure). This makes it prone to structure distortion and incapable of controllable noise synthesis. CycleDiffusion, on the other hand, completely lacks physics.

It’s apparent that current models struggle with the same fundamental issue: realistic noise modeling. Real CryoEM noise isn’t random static, it’s more a mix of electron-scattering patterns, radiation damage, and a ton of other background signals. And training models on synthetic data with simple Gaussian noise leads to pattern recognition not relevant to real experimental cryoEM data.

Here, CryoCCD aims to learn authentic noise patterns directly from experimental micrographs using diffusion models and apply that learned realism to physics-based synthetic structures.

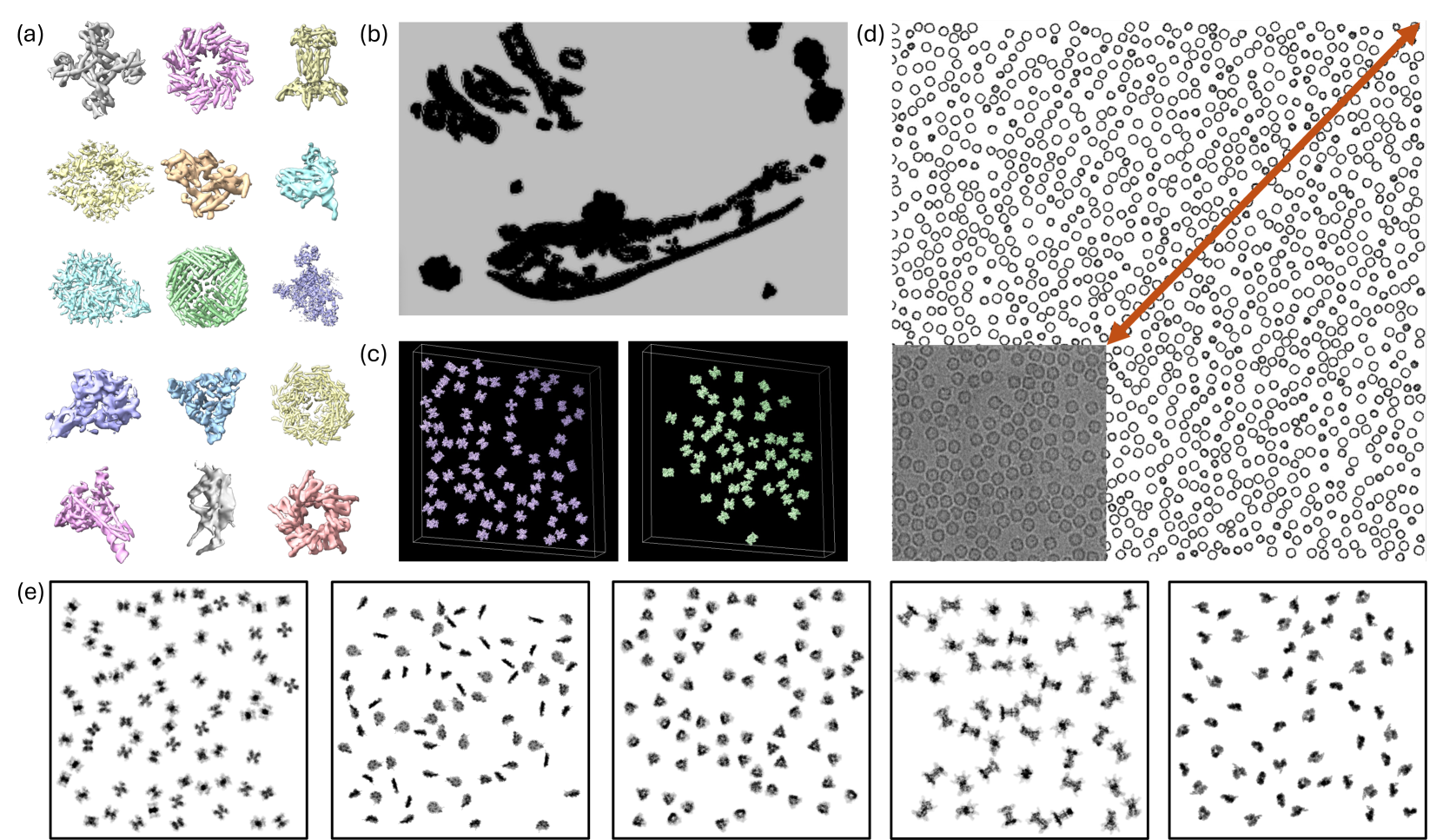

Diverse Structural Simulation

This is CryoCCD’s framework for synthetic generation from scratch. Basically a scene builder, and a really elegant one I find.

It begins by building a massive protein library using PDB and then subsequently AlphaFold to fill in gaps for proteins that haven’t been experimentally solved for. This is done to broaden the library’s heterogeneity and expose downstream diffusion models to a wider range of shapes/flexibilities.

It then embeds these proteins in realistic cellular contexts, taking real segmented cell volumes and using them as a backdrop for where the proteins will be placed. This placement is not just random scatter, they use two specific approaches:

Data-driven placement: taking real experimental data about where proteins actually sit

Biologically-informed synthetic placement: using rules about how different protein types behave in cells to place.

The framework also models class-specific distribution patterns: it allows for ribosomes to cluster like they do in real polysomes, viral capsids maintain realistic separation distances, and membrane proteins stay confined to organelle boundaries. The model is multi-scale as well.

An ice layer is simulated and includes realistic thickness variations and surface topography using Perlin-noise. Perlin, I learned, is also used in video game terrain generation.

Finally, to project, the total electrostatic potential from all embedded components is calculated, physics equations are applied, and the output’s filtered in Fourier space (for CTF) to yield noise-free, accurate micrographs.

Fig: The end result, generation of multi-scale synthetic data, of the framework explained above.

Fig: The end result, generation of multi-scale synthetic data, of the framework explained above.

Side Tangent b/c Fourier Space is Cool:

So what I’ve learned is that any image is made up of different spatial frequencies: low and high. Low = slowly-changing features, like overall shape of protein, while High = sharp changes, like maybe at the atomic-level

- Fourier filtering takes the 2D micrograph and transforms it, converting pixels to frequencies. Instead of having brightness values (x,y) like you would in a pixelated image, you have amplitude and phase for each spatial frequency.

- Apply the CTF filter by multiplying the CTF value with each frequency component. CTF of :

- +1 = frequency gets enhanced (bright ring)

- 0 = frequency gets cancelled (dark ring)

- -1 = frequency gets phase-flipped (contrast inverted)

- Apply the inverse of the Fourier transform to get back your filtered image, which shows the effects of microscope optics.

Conditional Cycle-Consistent Diffusion

The next step after synthetic generation is to subject them to realistic noise.

The DDPM takes images, gradually adds noise until they’re pure static, and reverses it to remove noise and recover a realistic-looking image. This results in the network understanding noise patterns and predicting what underlying images could potentially look like.

Note: this isn't just a denoising (noise --> clean image) process as it is also adding complex noise. CryoCCD is doing domain translation (synthetic --> realistic). As a result, without conditioning, the diffusion model might generate realistic images but with no respect to the original micrograph's particle placement, shapes, and background vs. foreground relationships.

Conditional Control

To address the issue of random generation, segmentation masks are used. In essence, create a mask showing where particles are vs. background in your synthetic image, feed the mask to the diffusion model along with the synthetic image, and the model learns to maintain particle placement/structural integrity.

Masks are also used for contrastive learning through defining anchors (foreground features), positives (other particle region features), negative (background region features).

Unpaired Data

This one is fascinating. Paired examples of synthetic micrographs and their real, experimental version don’t exist. So how would the model know if it’s translating correctly? The authors used cycle consistency:

Original synthetic → G_A→B → Realistic version → G_B→A → Reconstructed synthetic

Two generative models are at play, and the second, which reconstructs the synthetic image, is compared with the original to ensure that the A ⇒ B translation preserved all important structural information. Without G_B⇒A, you have no way to verify if G_A⇒B is working correctly. Information out = Information in.

Through training both models, you can measure cycle loss (||original synthetic - reconstructed synthetic||) and then use this loss to improve both models via self-supervised learning.

When loss is high:

∂L_cycle/∂G_A→B → "Don't move particles so much"

∂L_cycle/∂G_B→A → "Learn to better reverse the A→B translation"

When loss is low:

∂L_cycle/∂G_A→B → "You're preserving structure well, now focus on realism"

∂L_cycle/∂G_B→A → "Good job reversing, now be more precise"

So, to sum:

- conditional diffusion using segmentation masks

- cycle consistency

- contrastive learning

- multiple denoising steps to build up realistic noise patterns

Output: Synthetic micrographs that look like real experimental data.

Experiments

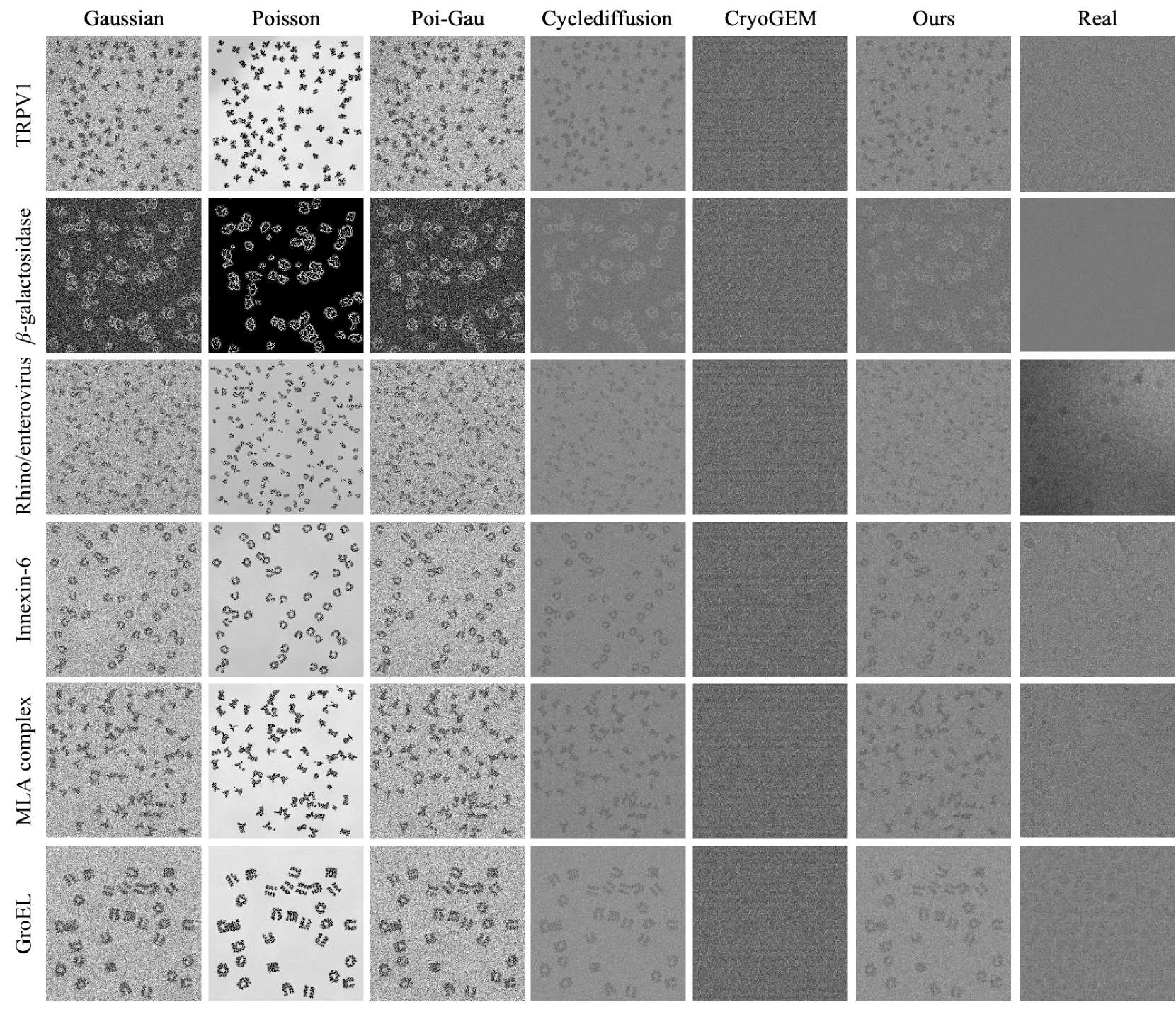

They trained CryoCCD using synthetic particles derived from 15 different EMPIAR datasets. For visual quality evaluation purposes, 6 datasets were chosen. Performance was evaluated against baselines — both traditional (Gaussian, Poisson, mixed) and deep generative (CryoGem, CycleDiffusion).

Eval 1: How Similar are the Generated Images to Real Data?

Average FID for CryoCCD at 18.45 was better than the others — ~314 for traditional (terrible), failed for CryoGem, and 22.67 for CycleDiffusion (close second).

Eval 2: Particle Picking

Basically, train Topaz (a particle picker) on synthetic data for each baseline+CryoCCD, then test on real experimental images. The question: “If I train an AI on synthetic data, can it successfully find particles in real experimental images?”

CryoCCD had the highest AUPRC across the board.

Eval 3: Pose Estimation

Train CryoFIRE (pose estimation method) on synthetic data with known orientations, then test on real images. Metrics included reconstruction resolution and accuracy of orientation predictions.

CryoCCD had the higher resolution and lower angular error across the board.

Eval 4: Ablation

Sampling steps study showed the goldilocks zone for number of denoising steps to be 10-20; sampling algorithms study showed DDPM (stochastic) being the best over DDIM for cryoEM as deterministic generation creates unrealistic uniformity.

- What stuck out to me here was how over-smoothing (higher denoising steps, specifically 20-50) provided diminishing returns and washed out fine details. However, 100 steps is enough to overcome this. So use either 10 steps or 100 :)

- I’ll dive into different algorithms for diffusion models in another post.

Quick Takeaways

CryoCCD’s architecture understands the subtleties of cryoEM noise and how diffusion models behave.

- I learned that even small changes in sampling strategy can have huge impacts on realistic image generation. Doubling steps resulted in a 13% worse FID score, and removing randomness (DDPM ⇒ DDIM) resulted in 6.5% worse performance.

- Speed and quality tradeoffs are quantifiable. And there’s still room for speed and quality improvements.

- Ablations are important.

- This can democratize synthetic cryoEM data.

I’m interested in seeing how this can be built upon and its implications in other domains, particularly scientific and medical imaging.